Our lives are shaped by countless obstacles to our desires. Many of these potential obstacles – race, gender, class, and the culture in which we reside, for example – exist largely outside our control. Awareness of this truth rarely deters our striving, however. We continue to climb, to throw ourselves against these limitations. Where our bodies meet their barriers, there is friction; in this friction, the potential for a story.

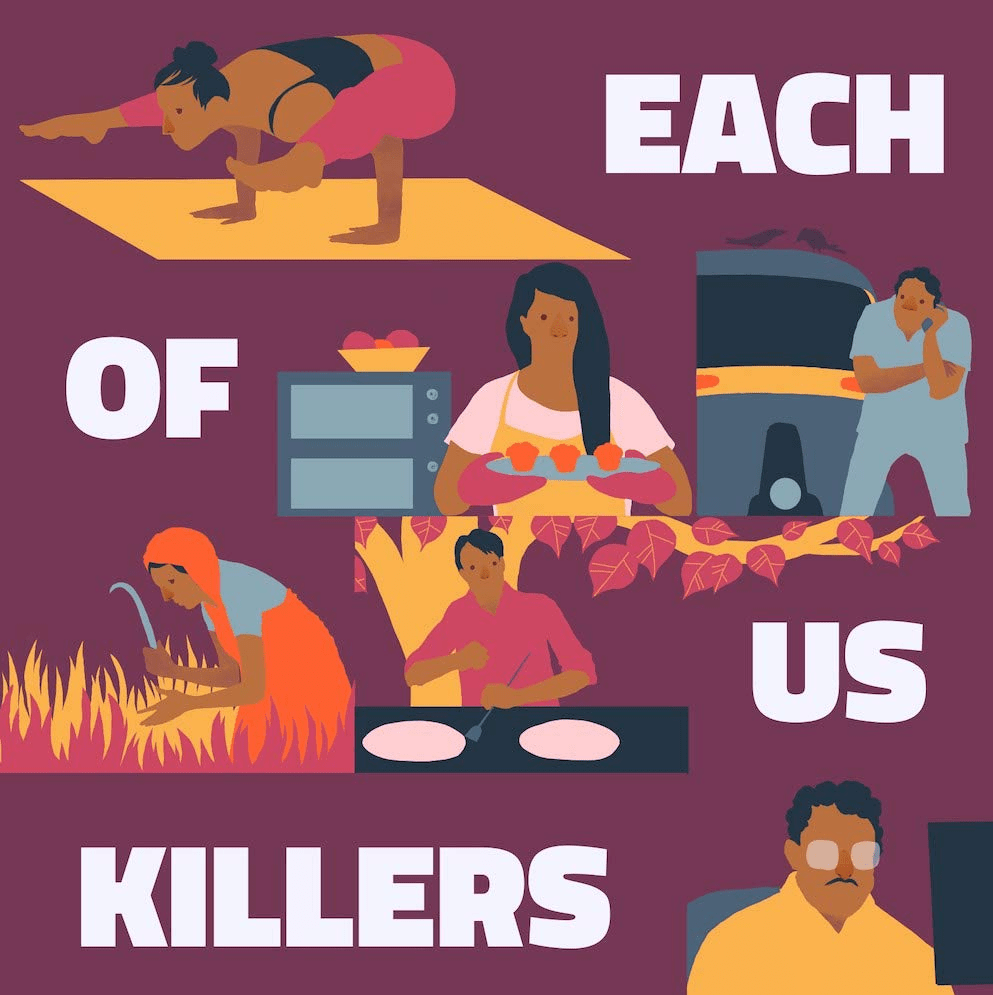

The characters of Jenny Bhatt’s debut short story collection, Each of Us Killers, all exist in the heat of this friction, bound by the constraints of their larger world. In “Journey to a Stepwell,” the protagonist Vidya requests to hear a story from her mother, but her underlying desire is for an answer; she must decide whether to keep her job and take a promotion, or bend to cultural expectation by following through on her engagement. There are no illusions about Vidya’s relative power in the situation. When she questions the nature of destiny, the third person narrator steps in to answer: “For women like her and Ma, [destiny] is simply a dagger thrown at you, which you must catch either by the blade or the handle. If you can figure out which end is which.”

Gender is also a fundamental theme in the story “Life Spring,” which follows a woman named Heena who has run away from an abusive marriage in the United States and returned to Mumbai, starting a bakery. Though her life is undeniably shaped and scarred by her history, a passionate encounter with a delivery man rejuvenates her, and directs her towards a new life for herself. But even this tryst is not simple for Heena, who must also navigate her life as a divorced woman, one who should not have “men, especially from lower-caste communities, coming and going at all hours.” She is harshly judged by her neighbor, and when she attempts to take out a business loan for a larger kitchen she is met with further discrimination. “A single woman on the wrong side of thirty was always a suspect liability,” Heena tells us, “more so if she was divorce-damaged or unfortunately widowed.” When she manages to open her new location, Heena’s success is made all the sweeter for the obstacles she overcame.

“For women like her and Ma, [destiny] is simply a dagger thrown at you, which you must catch either by the blade or the handle. If you can figure out which end is which.”

It’s not just gender that Bhatt is interested in investigating, however. Caste, social class, geographic location, and age are all featured in various stories throughout the collection, often illuminated through the lens of work. In “Pros and Cons,” a 45 year old woman’s position as a yoga instructor is used to highlight the feelings of failure and resignation that have accompanied her increasing age. In “Mango Season,” the sale of an expensive sari triggers a dream-like sequence in the salesman, in which he imagines his customer wearing the garment to an extravagant party. The colorful, cinematic imagery of his daydream contrasts with his life in poverty, but the salesman still takes some enjoyment in his work. The sale brings him “the joy of simply being alive in a world filled with undiscovered possibilities.” Work is a central part of who we are, Bhatt’s stories seem to argue, and thus crucial to any attempt to understand life’s many facets.

Though nearly every story shares some of these themes and motifs, Bhatt’s writing is far from formulaic. Formally, the pieces vary wildly. The opening story, “Return to India,” tells the story of a murdered software engineer through the lens of myriad interviews with the man’s coworkers, ex-wife, and murderer. The idea of collective witness is echoed in the closing, title story, in which the men of a poor village withhold details of a brutal crime from a visiting reporter. In the thirteen stories stuffed between these two, Bhatt also employs flash fiction, sequenced micro fiction, and a story in the form of a termination letter with “Separation Notice.” Even the aforementioned “Journey to a Stepwell” is complicated by a braided structure, the legend of four stuttering sisters interwoven with Vidya’s modern day plight. While inevitably some of these experiments feel more shallow than others, the overall effect of the variation across the collection is startling. There is a vibrancy in viewing the work as a whole, an excitement to finishing a story and wondering what the next will bring. This all makes Each of Us Killers as compulsively readable as it is sharp, and as enjoyable as it is thought-provoking; in short, an accomplished and impressive debut.

(7.13 Books, Short Stories, September 2020)

Keep up with Jenny Bhatt’s important news on her website www.jennybhattwriter.com and on Twitter @jennybhatt.

Jefferson Lee is a Korean American, born in a small town in Western New York called Canandaigua. He’s written short fiction for Maudlin House, non-fiction for The Rumpus, and is a student at the Writer’s Studio. He lives and writes in San Francisco. His Twitter handle is @jlee4219.