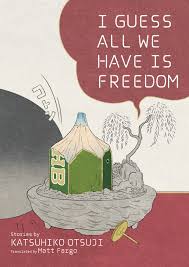

The world that we’ve created for ourselves is utterly radical. A house is radical. Moving spaces is radical. Movement is radical. But under the shadow of normalization, we don’t always notice just how radical they are. In his writings, Genpei Akasegawa disrupts this normalized understanding. In Matt Fargo’s English translation of Akasegawa’s short story collection I Guess All We Have Is Freedom, newly translated with Kaya Press, this magnifying glass is directed at everyday objects or activities, like new gutters, slamming a door, or getting a haircut.

The five short stories in Fargo’s translation may not seem radical at first glance. The stories reflect rather everyday occurrences such as going to the barbershop, cooking a stew, buying a new doorknob or gutters, or going to a cemetery. But Akasegawa’s astute eye helps us see the radical nature of all of these occurrences, bringing the reader to a state akin to when the mind wanders in the shower and starts to examine just how truly remarkable some of the most banal actions may be. Each story is a ‘glob of nitroglycerin in my hands. An icy brick of sleeping explosives. A bag packed with raw organic matter, just waiting to go bad. Unprocessed biomass, courting disaster…’

The narrators in these stories often try to share these perceptions with those around him. But few are able or willing to indulge his examinations. The incongruity of these conversations may be very familiar to some readers, that sense of trying to share a remarkable thought only to find that your partner in conversation cannot see this novel notion that you’re trying to share. Curiously, the one story that shows a symmetry in thinking patterns is the story ‘Symmetric,’ though this symmetry may be a result of the fact that the narrator is speaking with his daughter, and perhaps this pattern of thought has already been socialized into normalcy. But even she remarks at times, ‘What are you even talking about, here? But at least that’s better than the silence and the Huh? or Uh…okay?’ of the narrator’s companion in ‘And Dad Disappeared.’ Fargo’s translations render these conversations in such a tone that it feels like a conversation you could’ve had with a friend just yesterday. Or maybe you started talking into the phone and wondered why there was no response before realizing ‘that I forgot to dial. I picked up the receiver and started gabbing from the gun.’

Akasegawa’s stories, with all their seeming simplicity when it comes to their content, are brought into English with striking descriptions through Fargo’s translations. A family becomes a dying star, ‘a star gone into nova—its exterior layers blown out into the void, leaving only the white dwarf at its core.’ These space descriptions are used repeatedly, ‘as if the old black hole had formed again, ten years’ worth of time compacted so tightly that the little living room began to shine.’ Astronomical imagery occurs throughout Akasegawa’s stories. ‘I can almost see the image forming in his head: a never-diminishing mountain of junk. A junk black hole. Or the opposite of a black hole—a white hole.’ Perhaps space is far enough away and just unnatural enough to refuse our normalization, or at least perhaps it was at a time when the sky wasn’t filled with satellites and we could still see the splendor of the night skies.

As a Neo-Dadaist artist, Akasegawa’s eye is often drawn to everyday objects, objects that surround us but are rarely seen with fresh eyes. ‘Used books, magazines, scrapbooks, cameras, the lenses belonging to my cameras–they will all affix themselves to its walls like barnacles on the hull of a ship. Possessions, I realize, are barnacles. A house’s walls are a hull.’ Each one of Akasegawa’s metaphors pull the reader into the realization that nothing is as simple or banal as it might seem at first glance. Even the movement of a train can be striking if it goes in an outbound direction rather than inbound. ‘The train continues flipping through page after unexpected page of a city I thought I knew. This is a special moment. When a train goes the other way, you really feel like you’re moving. You get giddy.’

This ‘special movement,’ this idea of going the other way to really feel like one’s moving, this is at the core of these stories. Anything that you thought you knew or understood suddenly becomes something ever so slightly different, because it always was. You were just always looking at it from one perspective. And while the short stories don’t reach for the heights of absurdism, they are truly absurd because their narrators refuse to limit themselves to thinking in the typical fashion. ‘Moving the other way means you’re traveling; you’re on a trip. For example, um…imagine you’re at home. And you have to go to the bathroom. But instead of taking the direct path down the hallway, you climb up into the attic and then back down into the bathroom through a hatch.’ This line of thought isn’t always entertained by the narrator’s partners in conversation. ‘Man, you’re always so…radical.‘ Such a statement can feel dismissive, but normalcy always seeks to retain its control over the world. To push against this normalization will always result in dismissiveness, unless there is a shared desire to engage with the world in a new way.

Each story is striking in its rendition of everyday life, reminiscent of a collage as they recontextualize what is daily and banal in order to reveal its absurdities, though daily life has changed so much since Akasegawa was writing his pieces. Daily life moves faster than we expect it to. Many of these changes in life have already occurred even within the narrator’s lifetime in the story ‘And Dad Disappeared.’ ‘It used to be totally normal to see horses walking through town, just casually dropping horseshit in the middle of the street—plop, plop, plop.’

Fargo’s translation seems casual at first glance. When reading, it’s easy to continue tumbling through the stories. But the casual and conversational nature that he strikes throughout the stories sets the reader into a position of both familiarity and distance. To be both in the story and watching from afar. And it is in this multi-dimensional perspective that such everyday objects and interactions reveal different colors in their visual spectrum. ‘I give the tape a yank, and it screeches away from the styrofoam, sending ripples of sound through the kitchen.‘ Every sentence sends a ripple, reminding the reader of a similar encounter, instilling an awareness that nothing is ever so casual as it first appears. ‘You’re kicking the can. And as you continue to kick you realize that you’re not just kicking the can—you’re kicking the sound of the can.’

There is one story that bears resemblance to a mystery. Not everything can be easily understood, and ‘Oyster Season’ reminds you of this. While the rest of the stories hold the readers’ hand as you travel through the tale, pointing out this or that to notice, ‘Oyster Season’ throws reason into the distance and assures you that you’ll get there eventually, but you don’t quite know where you’re headed. And when a story ‘goes the other way, you really feel like you’re moving. You get giddy.’

Even the description of going to a barbershop in ‘To The Touch’ might reflect an initially odd paranoia but, in fact, truly underlines what a strange thing it is to go to a barber and trust a stranger with a knife to your throat. Combined with the narrator’s anxieties about getting a bad haircut, the act of getting a haircut and a shave is one of danger. Perhaps this statement might sound strange to the ear because what’s been normalized to our ears is the ordering of the words ‘shave and a haircut.’ But that’s what Akasegawa’s stories spark in the reader, a desire to start ‘moving the other way.’ Even if it means getting somewhere that you’ve been before.

Since Akasegawa first wrote these stories, perhaps nothing has changed more than the act of writing itself. Writing has always been radical. The mere fact of being able to turn one’s thoughts into a written representation, taking the ambiguity of our ideas and pinning them down into a representation that only reflects a piece of what we mean to say. But now writing’s radical nature has been supplanted by a new technology: LLMs, also known as AI. If anything, this makes the act of thinking and writing on one’s own even more radical than before. In the short story ‘Throes Of Home,’ Akasegawa suggests that ‘in this day and age, a gutter is the most radical purchase one can make.’ In writing this, I propose that in this day and age, writing one’s own words without the use of an LLM may turn out to be the most radical thing you can do.

Marina Manoukian reads, writes, and makes collage art. Marina is a queer Armenian based between Berlin, Germany and Boston, USA. Marina’s writing has previously been published with Full Stop Review, The Arts Fuse, The Baffler, LitHub, and others. You can find more of Marina’s words and images at marinamanoukian.com and at @crimeiscommon on Instagram