“Words are water” is a phrase that comes up repeatedly in Mina Ikemoto Ghosh’s novella Numamushi. Both words and water have the capability of being both beneficial and deadly to humans, and they both come in various forms that can be observed, deconstructed, and rebuilt. How words are used and examined can change depending on cultural and historical settings, but their impact on an individual’s life remains consistent.

Numamushi follows a boy who was found and adopted by a river guardian spirit in Japan following World War II. The titular boy is raised by the snake, or Father as he’s solely known, to shed his skin and hunt wild frogs and mice. It’s not until the boy meets a mysterious man named Mizukiyo who has moved into a supposedly cursed house near the river that his world begins to change. Now Numamushi has to understand curses, venom, language, and isolation in a tale that seeks to understand what is considered a curse and what it takes to not be consumed by one.

Ghosh’s novella begins with the immediate connection between the real and the fantastic, as Numamushi is an orphaned baby burned by napalm and left to be found by Father. Likewise, Mizukiyo and his friend Tora were both conscripted soldiers in the war, and while it’s been a few years since the war ended, every character is haunted and scarred by the war in some way. While learning to shed his skin has allowed Numamushi to heal, it becomes clear that the act of shedding is something that is both literal and metaphorical for traumatized people.

Likewise, the novella examines the power and knowledge that comes from reading and writing. Mizukiyo makes a living teaching calligraphy, and his lessons to Numamushi allow the boy to begin to understand the Japanese language. The two study how characters are formed and the roots and origins of these words for what they can mean in a deeper sense. As Mizukiyo was a former soldier and prison chaplain, he understands the danger and impact of words that led thousands of soldiers to their deaths, so to him, to understand how words are formed and used is to understand the power they hold.

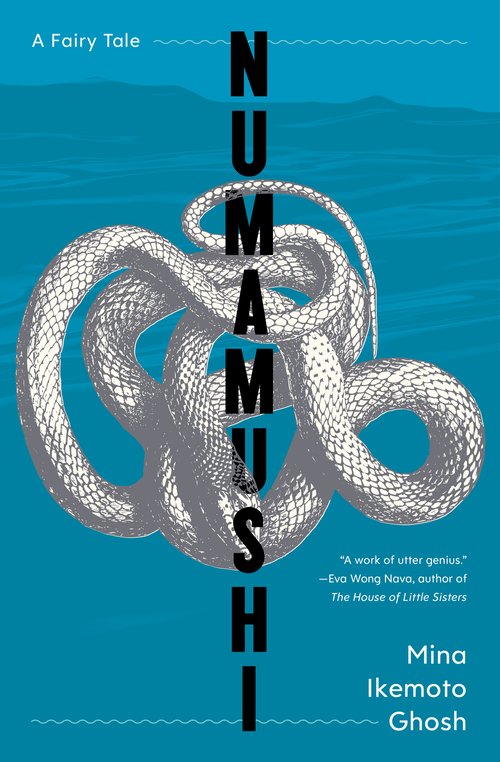

Ghosh’s novella is written as a fairy tale but takes its time to fill its pages with details and conversations to fully form the characters and the story. Throughout the novella are numerous ink drawings of snakes, as well as illustrations of key moments in the story. It’s Ghosh’s use of Japanese characters in calligraphy that shows the greatest impact of the language, as it allows the reader to really understand the design of each character and how they can be viewed and created.

Numamushi is an incredible debut novella that pulls the reader along the river as they observe this story of trauma, curses, and connections. It’s small in scope, but grand in its attempt to understand the power of words and how building connections with others left behind by an unpredictable world can lead to a renewal of spirit and body. Like how a snake sheds its skin, Numamushi reveals a new, pure story that is sure to be observed and appreciated by those who take the time to let it sit in their minds.

Alex Carrigan (he/him) is a Pushcart-nominated editor, poet, and critic from Alexandria, Virginia. He is the author of Now Let’s Get Brunch: A Collection of RuPaul’s Drag Race Twitter Poetry (Querencia Press, 2023) and May All Our Pain Be Champagne: A Collection of Real Housewives Twitter Poetry (Alien Buddha Press, 2022). He has had fiction, poetry, and literary reviews published in Quail Bell Magazine, Lambda Literary Review, Barrelhouse, Sage Cigarettes (Best of the Net Nominee, 2023), Stories About Penises (Guts Publishing, 2019), and more. For more information, visit carriganak.wordpress.com or on Twitter @carriganak.

Alex’s previous piece: In Review: Bodies of Separation by Chim Sher Ting (Issue 77)