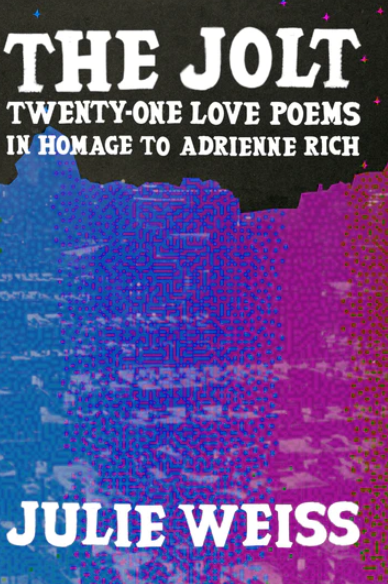

I wish I could quote for you the entirety of Julie Weiss’s chapbook The Jolt: Twenty-One Love Poems in Homage to Adrienne Rich (Bottlecap Press, 2023). Listen: “I want to remember you like this, / flushed in nothing but color: fuchsia, violet” (from XVII). Listen:

…On your lips

I taste the zesty beginnings of a coupletand don’t pull away, even when our tapas

arrive. How long before a body succumbsto hunger? Here’s to slowly eaten

delicacies. To days spent steaming.

(from VII). Listen: “I could howl / my devotion, and tomorrow, the valley / beyond the edge of the city would awake / in bloom” (from XVIII). I want to repeat and repeat these lush, unabashed images of love. I want to say Lucky Olga! (Weiss’s wife to whom this collection is dedicated), because, I mean, just listen: “Ask me if I’d walk a plank for you. Come, / sink me. Float me in your chambers” (“The Floating Poem”). Are you swooning? I am.

The Jolt unfurls a relationship across its 21 poems. The shape of the chapbook is in homage to Adrienne Rich’s Twenty-One Love Poems (originally published in 1976 as a limited edition chapbook and reprinted in The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974-1977). Some of Weiss’s lines are inspired by Rich’s language (and are so indicated in the notes to the collection), but these poems are not centos “after” poems. My sense is that Weiss used Twenty-One Love Poems as a container, a boundary within which she could roam.

Each of the poems in the chapbook is written in five sets of couplets, and Weiss uses this self-imposed restriction wonderfully. The tight container in which the language is held amplifies the expansiveness of Weiss’s diction; the emotion of the poems is constantly pushing to break off the constraint—much the way emotions, in the first flush of attraction and desire, push against self-control. Lush, image-laden language like “the sun-warmed lap of a Saturday / afternoon,” (VII) “an intoxication / of city nights,” (XIII) “the voluptuous Iberian night,” (XV) and “[f]ire orange, like a dawn bride” (XVII) attest to the poet’s rich and vibrant life, a vibrancy awakened by the beloved, while the couplets reenact the pairing that gives rise to the depth of emotion.

The tightness of the poems, the small space in which they move so grandly, also reenacts a continued reality for queer couples in public. Weiss writes “For all the gains this century, voices / hover below my own, like omens” (XI) and goes on to describe a long-time student who vanished when she “altered his assumptions” about her sexuality. In poem VIII she writes of a lesbian couple in London who was assaulted by a group of teenage boys who first demanded that the couple kiss for them. For all the gains, it can still be risky for a lesbian couple to be obviously, delightfully in love in public. Poem XVI speaks of an understated celebration in a restaurant (a proposal? I read it that way, but the cause of celebration is unnamed in the poem), and Weiss writes that later, when she writes a poem about the evening, she will “embellish the scene / with everything we hungered to do but couldn’t.” Couldn’t presumably because of the public nature of the restaurant. In poem XIV, a public kiss produces “a leer of ruffians.” The wildness of the love poems push back with exuberance against the restrains the outside world would place on queer couples, and the tight form Weiss has chosen for her poems embodies the tensions of this push-and-pull.

Weiss rejects the silence and “decorum” that queer couples and femme-presenting people more generally are expected to perform in public. In The Jolt, she claims the right to adore openly and wildly the beloved. “Because not even the next / minute is certain,” she writes in poem XVII, “I want to immortalize you // in a thousand glorious images” (XVII). She takes her place in the long tradition of love poems expressing gratitude and wonder that she too is a beloved, that lover and beloved found each other at all: “[e]xtraordinary, how the planets colluded / to lure us onto the same wrong train” (XX). Extraordinary, that twenty-one ten-line poems can reveal such deep emotion.

Jennifer Saunders (she/her) is the author of Self-Portrait with Housewife (Tebot Bach, 2019), winner of the Clockwise Chapbook Competition. Her poem “Crosswalk” won the 2020 Gregory O’Donoghue International Poetry Competition and was published in Southword. Jennifer is a Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, and Orison Anthology nominee and her work has appeared in Cotton Xenomorph, The Georgia Review, Grist, Ninth Letter, and other publications. Jennifer lives in German-speaking Switzerland, where in the winters she teaches skating in a hockey school.